Understanding criminal By Behavioural Analysis and the Prevention of Fraud

When a detective searches for a suspect’s motive, the detective is using behaviourist methods of analysis. The detective assumes that the suspect was stimulated by some arrangement of factors. Many courses in criminology are built around the fundamental premise that crimes are particular sorts of behaviour and best understood as the product of operant conditioning. Fraud examiners often use the same methods in approaching a case. When money is missing, the fraud examiner traces the known flow of funds and then asks, “Who had the opportunity and the motive to get at this money?” Even without being conscious of the fact, the fraud examiner is performing a behaviourist analysis on the crime.

Ultimately, the question of fraud and behaviour comes down to this : what can we do about it?

We know that people commit these crimes at an

alarming rate. Incidents range from the clerk who skims a few hundred dollars

off a business’s daily deposits, to multimillion-dollar scam artists who

destroy entire organisations. There’s a world of difference between the skimming

clerk and the scamming financial executive, so can we even analyse the two people

within the same system of fraud?

A fraud examiner working with behaviourist

principles knows that the difference between crimes lies in the different

behaviours. The man who plays million-dollar games with other people’s money is

stimulated and reinforced by a distinct set of factors, and so, too, is the clerk

who builds a family nest egg from his three-figure thefts. So when a fraud

examiner is asked to go beyond crime-solving and to consult on fraud

prevention, the job demands a thorough analysis of behaviour.

It is important to think of employment as a

system of behaviour because so much fraud occurs in workplace environments,

which highlights the connection between economics and people’s actions. For

both the crook and the dedicated worker, money exerts a powerful influence, and

this is not likely to change. The resourceful employer, then, should consider the

best way to establish a positive set of relations between employees and the

funds flowing through the company. The more rigorously we understand how people behave, the better equipped we are to

change the way they behave.

Behavioural studies such as those conducted

by Skinner show that punishment is the least effective method of changing

behaviour. According to Skinner, punishing brings a temporary suppression of

the behaviour, but only with constant supervision and application.

In repeated experiments, Skinner found that

punishment, either applying a negative stimulus or taking away a positive one, effectively

extinguished a subject’s behaviour, but that the behaviour returned when the

punishment was discontinued. In other words, the subject would suppress the

behaviour as long as the punishment was applied directly and continually, but

as soon as the punishment was withdrawn for a while, the behaviour was attempted

again; if there was no punishment following the attempt, the subject began to behave

as before.

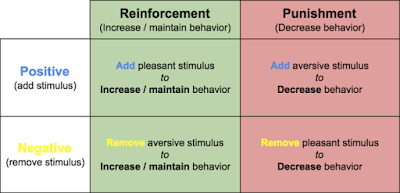

Reinforcement

and Punishment

Reinforcement and punishment of behaviour are

distinguished by the way that positive and negative forces are applied. A positive

reinforcement presents

a positive stimulus in exchange for the desired response. For example, a parent

might say to a child, “You’ve cleaned your room. Good. Here’s the key to the

car.” The behaviour (cleaning) is reinforced by the awarding of the positive

stimulus (the car key). In contrast, a negative reinforcement withdraws a negative stimulus in exchange for

the response. Continuing the example, the parent might say, “I’ll stop hassling

you if you clean this room.” The negative stimulus (hassling) is withdrawn when

the appropriate behaviour is performed. In an act of punishment, the polarities, so to speak, are reversed.

Faced with an undesired behaviour, the punisher applies a negative stimulus. A

father, hearing his son use profanity, puts a bar of soap into the boy’s mouth.

Punishment may also be administered by withdrawing a positive stimulus, such as

“Your room is still filthy, so you can’t use the car.”

Punishment fights a losing battle in

manipulating behaviour because it works by providing negative consequences, administering

penalties and taking away desirables. Access to the car or the thrill of a racy

story doesn’t become less attractive for its use in punishment; its power to

stimulate is simply squelched. Conversely, reinforcement proceeds to accentuate

the positive. Skinner concludes that behaviour is most effectively modified by

managing and modifying desires through reinforcement; he wants to replace destructive

behaviours with productive ones, instead of trying to punish an already

existing impulse.

Alternatives to

Punishment

Behaviourism points towards a number of

alternatives to punishment. Chief among these is to modify the circumstances surrounding the act. If an employee is

experiencing financial problems, there might be ways a company can help

alleviate pressures. For example, the company could offer financial

counselling, pay advances, or low-interest loans, thereby alleviating financial

difficulties without the employee having to resort to fraud. In other instances,

employees engage in fraud because they feel underpaid or unappreciated.

Emotions, according to Skinner, are a

predisposition for people’s actions. Anger is not a behaviour, but a state of

being that predisposes people to do things like yell or fight. Anger is a part

of a person’s response, to the extent that an angry man is more likely to get

in a shouting match with his friends. And since the emotional associations of

any event are important factors in conditioning behaviour, the associations can

be manipulated in conditioning the behaviour. That’s why advertisers use cute

babies to sell toilet paper, the image associates the toilet paper with the

emotions evoked by the baby. A company portrays its founder as a father figure

for a similar reason. When managers are faced with disgruntled employees, they

can modify these emotional circumstances, not just with “image” work, but with

adequate compensation and recognition of workers’ accomplishments. Incentive programmes

and task-related bonuses follow this principle, assuming that employees who feel

challenged and rewarded by their jobs will produce more work at a higher

quality and are less likely to violate the law.

Another non-punitive approach drives the

undesirable behaviour into extinction by preventing the expected response. This

is a specialised version of modifying the circumstances. Business managers

perform an extinction strategy by implementing a system of internal controls.

In requiring several signatures for a transaction, for example, a bank’s procedures

prevent any one employee from gaining access to money. This approach doesn’t involve

reinforcements or punitive measures; it simply modifies the structure in which

acts take place. The perception of internal controls provides a particularly

strong deterrent to fraud because it obstructs the operant behaviour that has,

heretofore, been linked with positive reinforcement. We prevent the act by

blocking the expected response. Criminal behaviour is discouraged because crime

doesn’t pay.

A related strategy overcomes improper

behaviour by encouraging the behaviour’s “opposite.” Skinner says we can condition

incompatible behaviour that interferes with the person’s usual acts. Instead of punishing a

child’s emotional tantrums, for example, the behaviourist rewards the child for

controlling emotional outbursts; we drive the tantrums into extinction by not

responding, thereby reinforcing the stoical behaviour. A destructive behaviour

is offset by an incompatible productive one. Since fraud involves dishonesty,

secrecy, and antagonistic behaviours, the astute manager finds ways to reward

the opposite behaviours, honesty, openness, and cooperation.

Of course, it’s easier to list these

strategies in a few paragraphs than it is to implement them.

Even the most seemingly simple acts can

become tangled as people and circumstances interact. A perfectly sound

theoretical reinforcement, an employee incentive programme, perhaps, might be viewed

with suspicion by disgruntled workers. Behavioural modification is never easy,

Skinner says; reinforcements “must be sensitive and complex” because people’s

lives are complicated and their behaviours sensitised. For example, people in

groups often interact in alarming and unstable ways. Skinner demonstrates this

tendency with the example of a whipping-boy game played by eighteenth-century

sailors. The sailors tied up a group of young boys in a straight line,

restraining each boy’s left hand and placing a whip in the right hand. The

first boy in line was given a light blow on the back and told to do the same to

the person immediately in front of him. Each boy hit the next in line, and each

one was hit in turn. As Skinner reports, “It was clearly in the interest of the

group that all blows be gentle, but the inevitable result was a furious

lashing.” Each boy in the line hit a little harder than

he had been hit himself; after a few cycles, the last blows would, in fact, be furious

(especially since each swing was preceded by pain, creating an emotional

disposition

of anger and anxiety). Whipping sessions

aren’t a likely happening in most companies, but people often exhibit a similar

inclination towards catalysed reactions: Whispering sessions gradually evolve

into full-blown discussions that echo into the hallways; minor financial indiscretions

grow into large-scale larceny.

Ideally, behavioural managers could

anticipate this catalysing and redirect the energies, but what if that is not

an option? Though the dollar amounts (and the audacity) of some whitecollar crimes

boggle the average observer’s mind, the crime remains an act of behaviour. The perpetrator

might be described as “obsessive” and “megalomaniacal,” but he is still

behaving in a network of actions, with his behaviour subject to operant

conditioning.

The monetary amounts are, in fact,

misleading. Once the stakes reach a certain level, it’s not even plausible to

look for explanations involving a lack of respect or appreciation. Highdollar criminals

describe their machinations as a “kick” or thrill; they feel like they’re

playing a game, and it’s the game of their lives. Behaviourists agree. Money is

a “generalized reinforcer,” directly linked with many positive factors and

often taking on a symbolic power of its own, thereby yielding a condition of

strength. Skinner says, “We are automatically reinforced, apart from any

particular deprivation, when we successfully control the physical world.” So, we need not be starving in order to act, especially with the sense

of control— symbolic and literal—gained by acquiring money. Game-playing exerts

something similar on its participants; someone who manipulates a chessboard or

a deck of cards successfully gains a sense of strength over external events. We

can play the game “for its own sake” because it yields the impression of

strength. Imagine, then, the behavioural stroke that happens when the game’s

power is combined with the power of money as a generalised reinforcer, and both

of these factors are played out with real people and settings. The dealmaker is

racing through a thicket of reinforcements, and the greater the risk; financial,

legal, or personal; the greater the thrill. The stimulus isn’t the money as a

thing in itself, any more than money for its own sake prompts the miser. In

either case, the condition of strength (we might even call it “power”) feeds

the behaving person; money just happens to be the reinforcer par excellence

of our culture.

Dealing with high-stakes criminals will remain

difficult, despite our understanding of their behaviour. Not just because the

amounts of money and the networks of action are so complex, but because the

conditioning is so intense. How, for example, can you replace the kick of

scoring a $35-million-dollar take in a three-day scam? Can a career con be

prompted to give up the deceitful practices that have marked his experience?

Finding genuine and specific answers might be delayed for some time, but they

will likely follow the same pattern we’ve discussed with other crimes, such as:

· Modifying the circumstances of the behaviour

by, for example, making legitimate businesses a more opportune place for daring

and innovative techniques

· Extinguishing the criminal behaviour by

preventing its success using regulation, controls, and supervision

· Encouraging behaviours incompatible with

criminal activity via educational practices and the demonstration of “values”

that call the criminal lifestyle, however flashy, into question.

The specific measures will be particular to

the crime. The actions dictate the response. But whether we’re dealing with a

working mother’s credit card fraud, or Bernie Madoff’s palatial schemes, our

methods can be behavioural. Fraud examiners might never eradicate crime completely,

but by approaching criminal acts scientifically, we can become more successful in

anticipating and preventing the acts.

Applying

Behavioural Analysis to Fraud Prevention

To successfully recognise, detect, and prevent fraud, the fraud examiner has to take into account as many variables as

possible, and has to learn a great deal about how human beings, as individuals

and in groups, behave.

All the efforts of behavioural engineering

notwithstanding, the question of behaviour finally rests with the person who

behaves. No substitute exists for the conscious individual making a choice to

act. And no science can predict or shape behaviour with pure accuracy. There

are just too many factors at work in the network of actions. However,

self-control is a behaviour that is guided by conditioning in the same way any

other act would be.

It does little good, for example, to tell an

alcoholic, “Stop drinking; control yourself.” The command alone has little

force, even if the alcoholic wants to stop drinking. Family members can suggest

that the man simply throw away his bottles, but “the principal problem,”

Skinner interjects, “is to get him to do it.” Family members can, however, help condition the alcoholic’s self-control

by registering disapproval of drinking, reinforcing the man’s successful

resistance to drink, and encouraging the man to do things incompatible with a

drinking life. They can’t follow the man through every step of his life; he has

to resist the impulse to sneak a sip on his own. But the behaviour of

resistance is strengthened by his family members’ intervention. “Self-control”

as a behaviour is shaped by “variables in the environment and the history of

the individual.” Understanding why people do certain things

allows us to go beyond a simplistic insistence that criminals “control

themselves.” We will instead have to consider how this control can be

conditioned, preventing the behaviour directly when possible, but ultimately

relying on each individual having adequately absorbed the principles of

self-control.